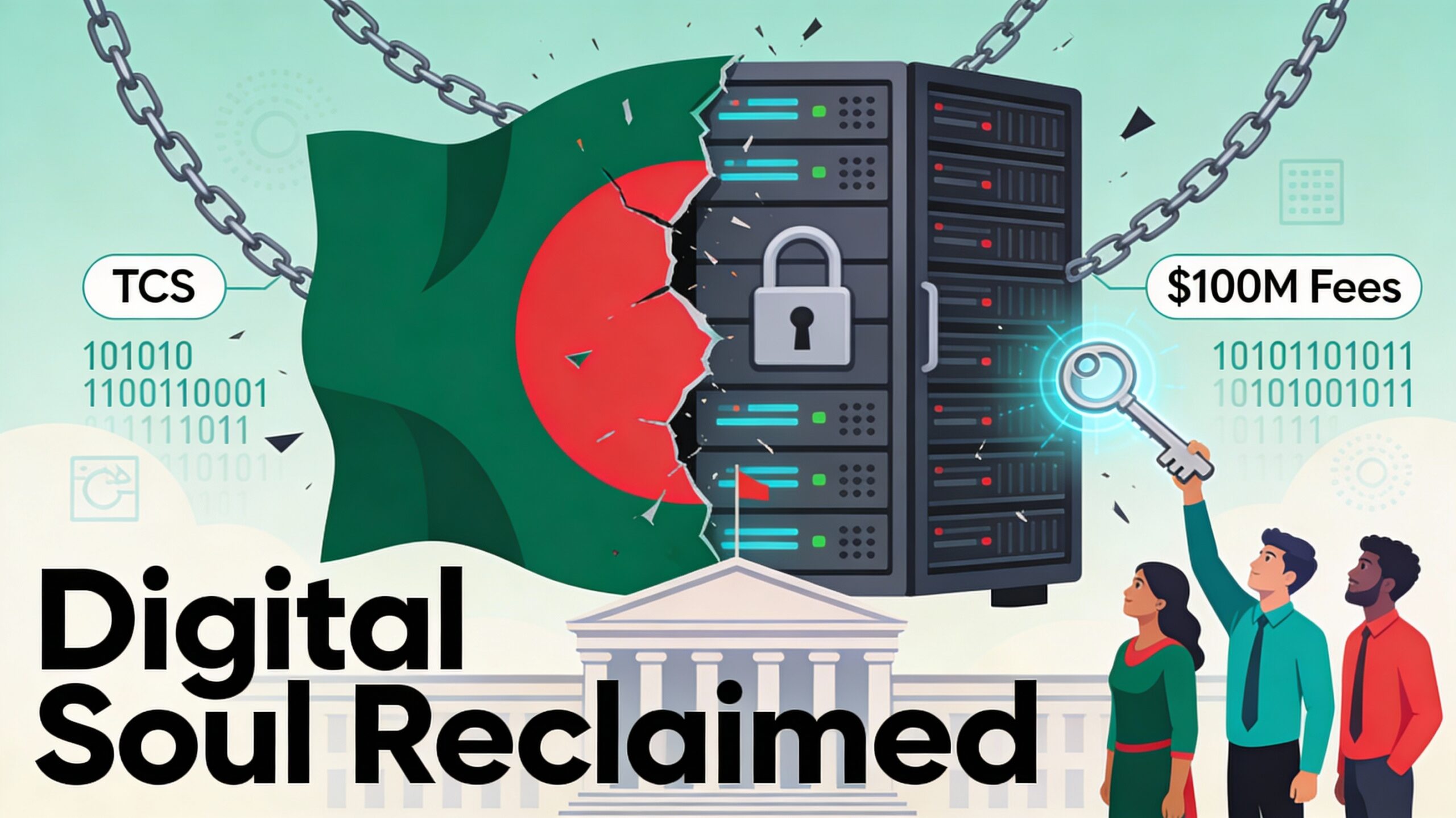

Bangladesh Bank Takes Back Its Digital Soul $100 Million Shift: Just Ditched Indian Banking Software

Bangladesh Bank just cut ties with India’s tech giant TCS after 14 years — but what forced this sudden digital rebellion? Discover how a young local team reclaimed control of billions, exposed hidden costs, and ignited South Asia’s quiet war for data sovereignty and financial independence.

What if your nation’s entire banking system — every balance sheet, password, and policy note — was managed on software built and controlled by another country? For Bangladesh, that’s not a “what if.” It was reality for fourteen long years. But now, just before 2025, something historic has happened: Bangladesh Bank has broken its high-tech dependency and taken back control of its digital heart.

This move might seem like a local IT switch, but dig deeper and it reveals a larger regional lesson that India — with its booming fintech economy, rising data bills, and expanding UPI ecosystem — cannot afford to ignore. Behind this bold pivot lies a dramatic story of data sovereignty, hidden financial costs, and an inspiring young ICT team that took on a multinational behemoth. The question is: what happens when a nation’s code becomes its currency of control?

The Hidden Drama: 14 Years of Dependency

In 2011, Bangladesh Bank outsourced its core banking operations — the system that records every interbank transaction, reserve adjustment, and cross-border remittance — to Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), one of India’s top IT firms. The contract seemed practical: TCS offered tested, stable software at a time when Bangladesh lacked in-house capacity.

But quietly, the dependency deepened.

Technicians from abroad reportedly had access to server-level credentials and database configurations, essentially holding a virtual master key to Bangladesh’s financial nerve center. For a sovereign central bank, that’s the equivalent of letting an outsider hold the vault combination.

By 2025, this raised red flags not only about cybersecurity but also about digital sovereignty — the right to control one’s critical systems and data.

How Big Was the Price Tag?

Between 2011 and 2024, Bangladesh Bank paid more than 1,000 crore taka (approx. ₹750 crore) to TCS for licensing, maintenance, and consultancy.

To put that in context, it’s enough to fund three new cybersecurity institutes or digitize 200 rural banks across Bangladesh. Critics say legacy contracts like these were symptoms of a broader problem: institutional inertia and elite lobbying.

Insiders allege that a syndicate of senior policymakers continuously delayed the local transition. The motive? Influence and opacity. Foreign dependencies enabled transactions that were expensive, slow to audit, and, most importantly, beyond public scrutiny.

The Turning Point: Inside Team BCBICS

In 2022, a small team of Bangladeshi ICT professionals quietly started building BCBICS (Bangladesh Core Banking and Information Control System). Trained under the government’s “Digital Bangladesh” initiative, these developers combined open-source technologies, regional APIs, and AI-based fraud detection tools.

For months, BCBICS ran in parallel with TCS’s system — handling mock transactions, reserve updates, and simulation drills. The results impressed auditors. On 18 December 2024, Bangladesh Bank officially announced that its old system would be shut down permanently.

Experts estimate the shift will cut foreign software costs by 80% annually, freeing funds for cybersecurity, local skill-building, and AI-driven analytics for monetary policy.

Why India Should Pay Attention

At first glance, this looks like a Bangladesh-specific story. But under the surface, it raises pressing questions for India’s own data sovereignty and financial autonomy in a world increasingly run by code.

1. Fintech Boom, Hidden Risks

India’s fintech scene — from UPI and Account Aggregator (AA) frameworks to Digital Rupee (CBDC) pilots — sits atop massive data exchanges. While UPI is Indian-developed, many allied systems (from cloud storage to security modules) use foreign APIs or dependencies on AWS, Oracle, or Microsoft Azure.

If a central authority like RBI or NPCI ever lost control of these layers, it would jeopardize not just financial transactions but also national security.

2. RBI’s Push for Local Control

Since 2023, RBI has repeatedly emphasized “data localization” in payment regulations. It mandates that all payment system data must be stored only in India. The Bangladesh episode strengthens RBI’s argument for tighter domestic control — reminding policymakers that sovereignty in finance means sovereignty in infrastructure.

3. Lessons for India’s Private Sector

Indian banks, despite pioneering digital innovation, still outsource large-scale IT operations to multinational CRM and cloud platforms. Bangladesh’s pivot offers a wake-up call: the future of finance isn’t just about who offers the fastest app, but who writes the source code behind it.

The Sovereignty Economy: Code, Control, and Currency

In 2025, we’re witnessing the rise of an economic model where digital sovereignty equals financial stability. Let’s unpack that for Indian readers who straddle between innovation and regulation.

| Concept | Meaning | Why It Matters |

| Digital Sovereignty | Control over national data, tech infrastructure, and source code. | Protects against espionage, manipulation, and cyber threats. |

| Core Banking Independence | Owning in-house systems for inter-bank and inter-country transactions. | Cuts costs, boosts transparency, ensures compliance with local regulations. |

| RegTech (Regulatory Technology) | Using AI and analytics for compliance automation. | Helps banks adapt quickly to RBI rule changes and prevent leaks. |

India is already experimenting with RegTech frameworks, AI-based audit trails, and account-level blockchain authentication. Yet, Bangladesh’s case shows that policy is only half the solution — the real transformation happens when local engineers have full root access to their nation’s systems.

Shadow of the 2016 Cyber Heist

To fully grasp Bangladesh’s urgency, remember the Bangladesh Bank cyber heist of February 2016. Hackers infiltrated the bank’s systems via compromised credentials and nearly stole $951 million from its New York Federal Reserve account. While most transfers were blocked, $81 million disappeared through casinos in the Philippines.

Forensic investigators alleged weak internal IT security and excessive reliance on foreign-managed systems. That trauma seeded the decision to rebuild — and reclaim control.

This echoes India’s growing cybersecurity focus under CERT-In and RBI’s 2024 Cyber Security Framework, which mandates continuous monitoring of data centers and privilege access systems. The Bangladesh shift, therefore, acts as both a cautionary tale and a success story for regional cybersecurity.

Five Lessons for Indian Banks and Policymakers

Here are five concise, high-impact lessons tailored to Indian banks and policymakers, drawn from Bangladesh Bank’s BCBICS shift and India’s latest RBI directions on IT outsourcing and cybersecurity.

1. Treat core banking code as sovereign infrastructure

Indian banks must view core banking software and payment rails as “strategic infrastructure,” not just IT projects, ensuring ownership of source code, architecture visibility, and the ability to switch vendors without losing control of data or operations.

2. Reduce risky long-term vendor lock‑in

Bangladesh’s 14‑year dependence shows how multi-decade outsourced contracts can create hidden costs and opaque influence networks. RBI’s 2023 IT Outsourcing Directions push Indian regulated entities to build clear exit strategies, periodic vendor reviews, and sunset clauses to avoid lock‑in.

3. Make data localization and access control non‑negotiable

By moving to BCBICS, Bangladesh Bank restored exclusive control over server access, configurations, and sensitive financial data. Indian banks must fully align with RBI data localization and cybersecurity frameworks, enforcing strict privileged-access management and ensuring that no foreign vendor can access production data without granular, auditable controls.

4. Invest in in‑house tech talent and public digital stacks

A young internal ICT team enabled Bangladesh to replace foreign software with a homegrown core system. Indian policymakers can deepen the India Stack model into a “Banking Stack,” funding internal engineering teams in PSU banks, shared utilities, and open APIs that reduce dependence on proprietary foreign platforms.

5. Link procurement to transparency, cyber‑resilience, and policy goals

The Bangladesh case surfaced questions about who benefited from prolonged foreign reliance and high service fees. Indian regulators can tie tech procurement to measurable outcomes: mandatory cyber‑resilience benchmarks, public disclosure norms for large IT contracts, alignment with RBI’s cybersecurity framework, and independent audits of high-risk outsourced functions.

Actionable Personal Finance Takeaways

Here are focused, India-specific, do-it-now money moves inspired by the Bangladesh Bank story, aligned with current RBI rules and fintech realities.

1. Clean up your app list

- Delete lending or finance apps not clearly regulated by RBI or partnered with a bank/NBFC; unregulated apps are a major 2025 crackdown area under RBI’s Digital Lending framework.

- Prefer UPI and wallet apps with strong market presence and compliance track record (PhonePe, Google Pay, Paytm, leading bank apps), which must follow RBI data and security rules.

2. Lock down your financial data

- Turn off unnecessary permissions (contacts, SMS, call logs, file access) for payment and lending apps; RBI’s guidelines explicitly warn against over-collection of customer data.

- Enable 2FA, app locks, and device screen locks for all banking, UPI, demat, and investment apps to reduce account-takeover risk as digital payments surge.

3. Choose “India-first” rails for daily money

- Route everyday payments (Bills, rent, transfers) via UPI, RuPay, or bank apps that store and process transaction data in India, as mandated by RBI’s data localization rules.

- When using international fintechs or cards, treat them as “use-with-caution” tools for travel or specific needs, not your default for savings or primary transactions.

4. Borrow only from fully compliant lenders

- Before taking a personal loan or BNPL, check if the lender is listed as a regulated entity on RBI’s website or in the app’s official disclosures; RBI now expects direct fund flow between lender and your bank, not via obscure intermediaries.

- Avoid apps that: hide total cost, ask for full contact access, threaten during recovery, or push instant top-ups aggressively—behaviours flagged in RBI’s digital lending and consumer protection alerts.

5. Build a “sovereign” personal finance stack

- Keep salary, emergency fund, and long-term investments (FDs, mutual funds, PPF, NPS) with Indian banks and SEBI-regulated intermediaries, which must follow Indian data, KYC, and dispute-resolution laws.

- For diversification (global ETFs, foreign apps, crypto-like products), cap exposure to a small percentage of your net worth and track changing Indian regulations closely as RBI and SEBI tighten oversight.

The Untold Side: Who Benefited for So Long?

Inside Bangladesh Bank, many whisper about a deep-seated ecosystem that benefited from the 14-year dependency. Long-term contracts often breed procurement cycles laced with “consultancy overheads” and “support extensions.”

It’s not unique to Bangladesh. India itself wrestles with similar challenges in public-sector technology — from cloud subscriptions to defense software deals that keep renewing without transparency.

As public accountability movements and Right to Information (RTI) demands grow, citizens across South Asia are beginning to question how foreign IT contracts shape national decision-making.

Why This Move Resonates Emotionally

Look beyond the hardware and code — this is the story of a nation reclaiming confidence.

For millions of young Bangladeshis, BCBICS is a symbol that local talent can replace foreign expertise. It’s about pride, trust, and freedom from dependency — concepts that strike a chord with India’s own Digital India vision.

The emotional power of this shift lies not just in cost savings, but in the assertion that digital sovereignty is self-respect coded in binary.

Final Thought

Bangladesh Bank’s bold leap from dependency to autonomy isn’t just a story of software — it’s a blueprint for nations seeking control in a data-driven world. As India expands its financial frontier through UPI exports, CBDCs, and digital regulation, the real question is no longer who builds faster systems, but who commands the source code of sovereignty.

For Indian policymakers, this is a wake-up call — to strengthen local capacity, audit foreign dependencies, and treat technology as a layer of national defense. For ordinary citizens, it’s an invitation to rethink digital trust — who holds access to our data, credit history, and savings.

The next frontier of economic power won’t be decided in boardrooms or ballots, but in data centers coded with national integrity. And as South Asia reclaims its digital independence, the most critical file may not be a document — but a line of code.